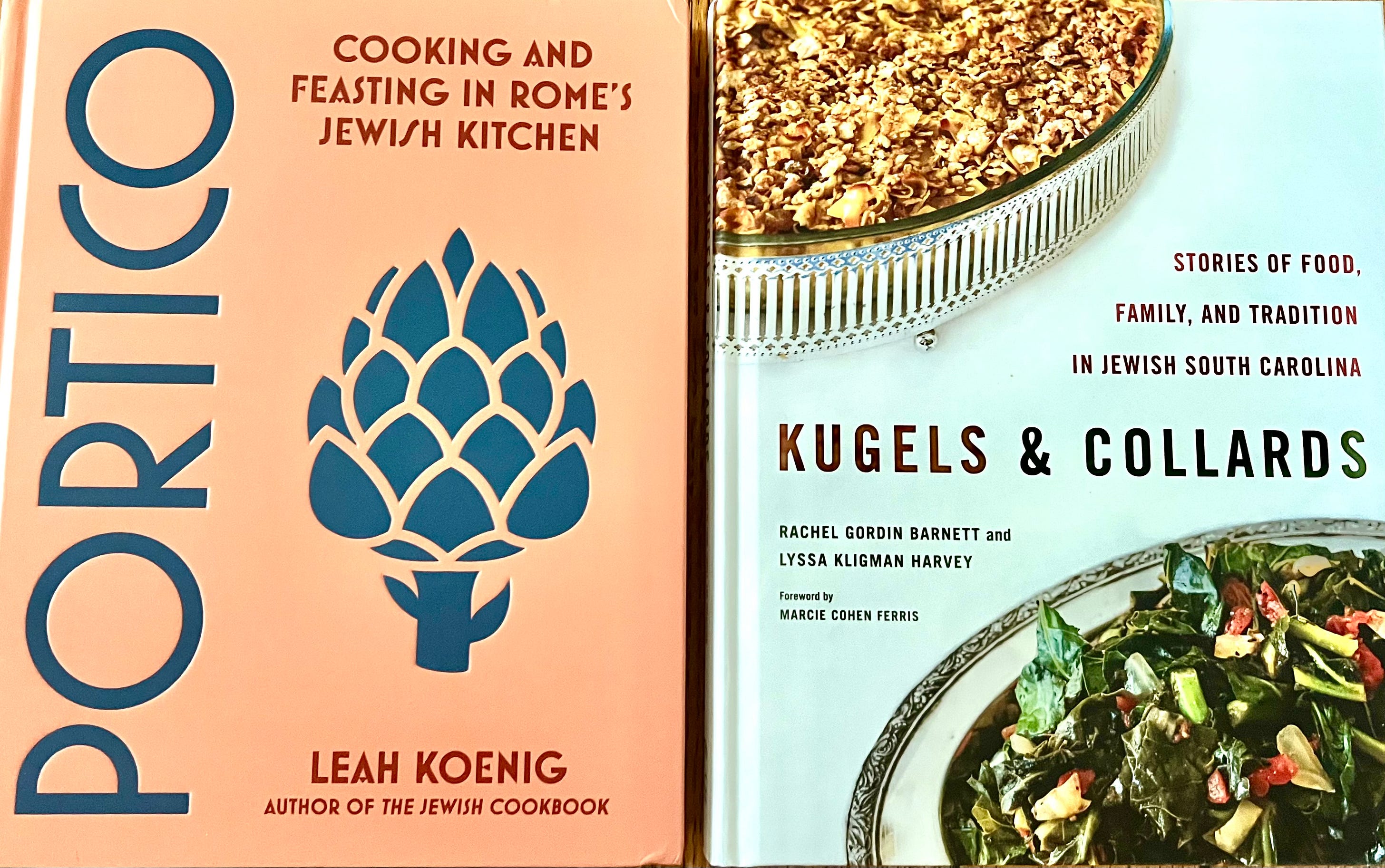

Thank you for reading Between the Layers! If you’d like to support my work please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Meet Two New Jewish Cookbooks I Love - No. 239Portico and Kugels & Collards are as much about culture and history as they are fabulous recipes to make this fallYOU DON’T HAVE TO BE JEWISH to enjoy two new cookbooks. One was on my radar as I met its author, Brooklyn-based Leah Koenig of The Jewish Table, during Substack’s food writers’ initiative last year. Leah’s much-awaited Portico examines the distinct and captivating Jewish cooking and baking of Rome. The second book, Kugels & Collards, weaves together first-person stories and recipes of Jewish cooks throughout South Carolina. Its authors, Rachel Barnett and Lyssa Harvey, are lifelong South Carolinians and community volunteers who have been writing about the intersection of Jewish and Southern cooking in a blog called Kugels & Collards, from which this book was born. I share a fabulous zucchini recipe today from Portico, and next Tuesday, I bake a cheesecake from Kugels & Collards. While set worlds away, Kugels & Collards and Portico are both about preserving food history.At the center of Portico is the Ghetto, the walled and cramped slum where for 315 years, Rome’s Jews were forced to live. Jews who came to Rome over the centuries brought with them ingredients and culinary methods of the homelands they left behind. They were the Italkim from Jerusalem, and later, as a result of the Spanish Inquisition, the Sephardi Jews of Spain, Portugal, southern Italy, and northern Africa. The intertwining legacy of Jewish and Italian cooking dates back more than 2,000 years. Perhaps the most iconic food of the Ghetto became the fried artichoke, symbolic if you think about it, because the artichoke, like the Jews, was discarded. It wasn’t used much in cooking until the Sephardi Jews carefully cleaned and trimmed its tough exterior before frying in olive oil until crispy and delicious. Have you savored the fried artichokes in Rome?Other legacies from Sephardi cooks, says Leah, were incorporating ground almonds in cakes and enlivening savory dishes with raisins and pine nuts. In Rome there was resiliency that came out of strife, creating a “beguiling cuisine.”Appropriately, Portico opens with Vegetables (Verdure) and then proceeds to Soups (Zuppe), Fritters (Fritti), Pasta and Rice (Pasta e Riso), Main Dishes (Secondi) and Sweets (Dolci). Flipping these pages, I want to make everything. Leah’s interest in Roman Jewish cooking began when she and her husband Yoshie honeymooned in Rome in 2009 and were invited to a traditional Shabbat dinner. The food was ‘’completely unlike the Eastern European Jewish dishes I had grown up with. But somehow, everything tasted like home.’’ And it was all about olive oil. ‘’I had multiple people express to me how olive oil was something of a lifeblood to Rome’s Jews during difficult times—an accessible source of joy that helped them get through the centuries of discrimination and hardship,’’ she says. ‘’One woman told me, ‘If you see a layer of olive oil glistening on top of your soup, that is how you know you’ve added enough.’ I love thinking about how something as simple as olive oil could provide them that sense of security and comfort.’’ Leah wrote much of the book during the Covid lockdown, and when travel restrictions eased, she and photographer Kristin Teig headed to Rome to find the people, restaurants, and markets to bring her book to life through photos. In South Carolina, there was adaptation, a love of local ingredients, and the assistance of African-American cooks.According to the Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina, Charleston was an important port city where Jewish immigrants began arriving as early as the 1690s. They were drawn by the promise of economic opportunity and the town’s reputation for religious freedom, and as late as 1820, Charleston was home to the largest Jewish community in the United States. Many of these early Carolina Jews were Sephardi as well as Ashkenazi, and later, were descendants of Holocaust survivors. More recent newcomers have come from Russia and Israel. The chapters are arranged under themes such as the journey, traditions, holidays, cooking like the neighbors, and fundraisers. At the front of the book, Jewish scholar Marcie Cohen Ferris writes the foreword and eloquently explains the Jewish culinary culture in the South. Of which Rachel Barnett’s paternal grandfather, Morris Gordin, was a part. He opened dry goods stores in Summerton and Pinewood, both farming towns, in the early 1900s and supplied locals with everything from church clothes to farming overalls. His wife, Sarah, was active volunteering in the Jewish community and developed a strong friendship with their African-American cook Ethel Mae Glover who came to work for the family in the 1930s. She like other Black cooks introduced Jews to fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, and collard greens. She cooked the collards without pork to adhere to the family’s ‘’semi-kosher’’ diet, Rachel says. And that is just one of the many charming stories in this book including how traveling Jewish salesmen acted as matchmakers and stayed in local Jewish boarding houses, a chocolate roll became unique to Sumter and the Upstate region, Lyssa Harvey’s grandmother Ida’s Lithuanian kugel recipe was revived for Rosh Hoshanah for a new generation, and the cake-decorating grandmother who raised her own chickens and then drove them to the nearest kosher butcher in Augusta, Georgia, in crates tied to the top of her car. Let’s cook! One of Leah’s favorite recipes in Portico is Pomodori a Mezzo, roasted tomato halves doused with olive oil, sprinkled with salt, sugar, and garlic, and then roasted until they fall apart.‘’The flavor coaxed out of the tomatoes is incredible,’’ she says. ‘’I think that dish really embodies what Roman Jewish and much of Italian food is at its core—simple and elemental, but high impact in terms of flavor and comfort.’’ While Italians use Casalino tomatoes—round, slightly flat and ribbed like a mini pumpkin—I had a few ripe Better Boy and Cherokee purples, and they worked just as well. You cut the tomatoes in half in the middle, squeeze out the juices and seeds into a bowl like you are squeezing a lemon—I made a quick pasta sauce from the juices!—and then place them in a baking dish brushed with olive oil. Sprinkle with minced garlic, a little sugar, kosher salt, and pepper, then drizzle with more olive oil. Roast at 375ºF for 30 minutes, then give the pan a shake to keep them from sticking, and roast another 40 minutes, or until they begin to collapse and are sweet as candy. And after you remove the tomatoes from the oven, shower them with chopped basil and serve alongside roasts, with pasta, or just crusty bread. “If you keep a jar of concia in the refrigerator during the summer, you will always have something delicious for making sandwiches and pasta,” - Daniela Gean, a restaurateur in Rome’s Monteverde neighborhood.‘’She’s right,’’ says Leah in Portico. The dish of pan-fried zucchini (concia) marinated in vinegar, garlic, and fresh herbs is found everywhere in Jewish Rome because it is both delicious and useful. ‘’The dish’s name stems from the act of hanging clothes out to dry, the same way that the sliced zucchini is dried before it is fried. Some home cooks leave the zucchini in the sun for half a day or more,’’ she adds. But up to an hour stacked between paper towels in your kitchen works, too. And while Roman Jews use the striped, light and dark green zucchine romanesche for their concia, she says our regular zucchini works, too. That’s what I used. It was so good that there were no leftovers for tucking with slices of mozzarella on a sandwich the next day as suggested. Maybe next time. Which proved what I knew: You don’t have to be Jewish to appreciate the stories behind the recipes in these two books just released today. Next Tuesday I will share Eleanor’s Cheesecake recipe and a little more about Jewish baking. Here is how to get your own copy of Portico and Kugels & Collards. Have a good week! This Thursday for paid subscribers, I rebake the 1960s dill bread that once captivated America and give it a more modern spin.

THE RECIPE: Silky Marinated Zucchini (Concia)I immediately fell in love with this recipe. I had fresh zucchini, maybe not the same variety as in Rome, but locally grown. Snipped off the ends, and ran them across the mandoline so they were about 1/4-inch thickness. Then I blotted them with paper towels to draw out moisture as Leah directs. I heated olive oil in large skillet and began frying the strips, making sure to cook them several minutes before turning just once. They were soft and lightly browned around the edges. You scatter on minced basil, mint, and garlic, followed by salt, pepper, and red wine vinegar, which acts as a marinade. Store them at room temperature to fold onto toasted bread for a sandwich or to adorn pasta for dinner. There are so many yummy uses for concia. Serves 4 to 6

Slice the zucchini into ¼-inch thick (6mm) planks or rounds. Lay the zucchini on a paper towel-lined baking sheet and let rest for at least 1 hour to draw out some of the moisture. (Use a second baking sheet if they don’t all fit in one layer.) Stir together the basil, mint, and garlic in a small bowl, and set aside. Heat the oil in a large frying pan set over medium heat. Working in batches, fry the zucchini, turning once, until softened and lightly browned on both sides, 3 to 5 minutes per side. If the pan begins to look dry, add another tablespoon of oil as needed. The zucchini tends to sputter a lot; use a splatter screen to keep the oil in the pan. As each batch of zucchini is fried, transfer them to a small baking dish and sprinkle with a bit of the herb mixture, vinegar, salt, and pepper. Gently toss to combine, then continue adding fried zucchini and the remaining ingredients until everything is used up. Let the zucchini sit at room temperature, basting occasionally with the juices from the baking dish, for at least 30 minutes before serving to allow the garlic to soften, and the flavors to meld. Just before serving, taste and add more salt, if needed and, if desired, drizzle with a little more olive oil. Store leftovers, covered, in the fridge for up to 3 days. You’re on the free list for Anne Byrn: Between the Layers. If you’re liking what you’re reading, why don’t you become a paying subscriber for more recipes, stories, and content. |

0 comments:

Post a Comment